Blog

Adventures in Nature

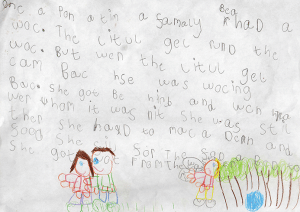

As children we would dream of having adventures like the Swallows and Amazons: when their summer holidays came round the Walker children would spend it camping on an island in the middle of a lake. With no adults on hand and just the cavalier parental advice that ‘if not duffers, won’t drown’, they spend their holidays having adventures in boats and sleeping under the stars. (more…)

As children we would dream of having adventures like the Swallows and Amazons: when their summer holidays came round the Walker children would spend it camping on an island in the middle of a lake. With no adults on hand and just the cavalier parental advice that ‘if not duffers, won’t drown’, they spend their holidays having adventures in boats and sleeping under the stars. (more…)

You’ve got to respect the Elder tree; vitamin-rich berries, gnarly climbable branches and brittle sticks of kindling that will get the fire going – it’s the tree that keeps on giving throughout the year, but its at its finest right now in June with its white froth of perfumed blossom filling up the hedgerows.

You’ve got to respect the Elder tree; vitamin-rich berries, gnarly climbable branches and brittle sticks of kindling that will get the fire going – it’s the tree that keeps on giving throughout the year, but its at its finest right now in June with its white froth of perfumed blossom filling up the hedgerows.

We’ve been bending over backwards to try out new ideas with flexible materials this April. Spring hasn’t quite sprung for us here yet (still snowing at the end of April!) but a plentiful supply of willow rods and bramble stems has provided a flexible resource that keeps on giving.

At end of March my Dad presented me with 2 buckets full of fresh willow he had chopped back from his hedge. Taking this to our Easter holiday forest schools the children soon got to work experimenting and making. The flexibility of willow meant some got snapped up for making bows and arrows, although we don’t think its as good as hazel for strength under fire. The bendiness lends itself well to some creative ideas though, and forest school practitioner Ruth McBain showed us an owl she’d made by tying up curved shapes with wool. A few forest school-ers soon wanted to make one too. (more…)

At end of March my Dad presented me with 2 buckets full of fresh willow he had chopped back from his hedge. Taking this to our Easter holiday forest schools the children soon got to work experimenting and making. The flexibility of willow meant some got snapped up for making bows and arrows, although we don’t think its as good as hazel for strength under fire. The bendiness lends itself well to some creative ideas though, and forest school practitioner Ruth McBain showed us an owl she’d made by tying up curved shapes with wool. A few forest school-ers soon wanted to make one too. (more…)